In our most recent blog post series that we’re calling Illustrating Our Process, we’ve been looking at each of our design phases through the lens of different visual tools we use. We’ve made it through all of the steps of the design process – Schematic Design, Exterior Design Development, Interior Design Development and Construction Documents – and are moving into the most exciting part of our work – construction! This week, we’re discussing the first phase of getting a Contractor involved – Bidding! We will also touch on Value Engineering and Permitting.

When Does Bidding Happen?

It depends on the project! Sometimes, we go out to bid very early, around the point where we have about 25% of Construction Documents complete. This generally happens when we want to get a very rough estimate of how much the house might cost. This can be helpful for clients who are trying to keep a tight budget, but it does mean that we tend to pause drawing to wait for bids.

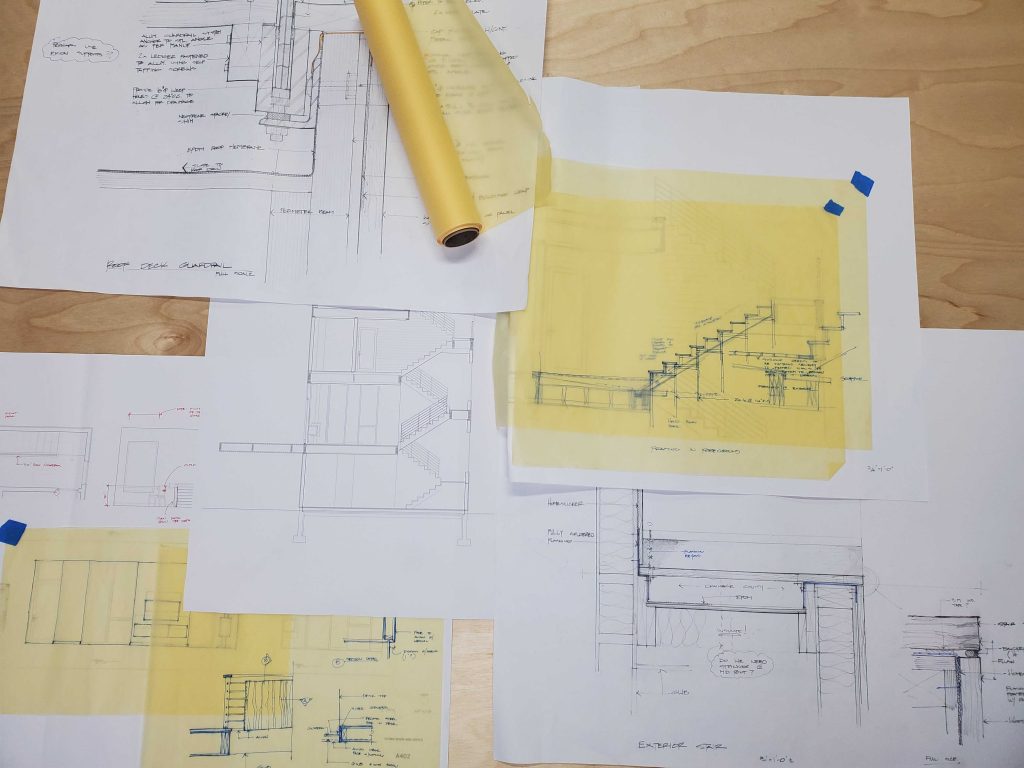

A more typical approach to bidding includes more complete Construction Documents – typically around an 80% CD set. We coordinated this set with our structural engineers. It also includes information about mechanical, has additional building and wall sections and typically includes some quantity of details. This set gives bidders a more complete picture of the house. Clients can therefore expect a more accurate price on the project.

What Can Clients Expect To See On a Bid?

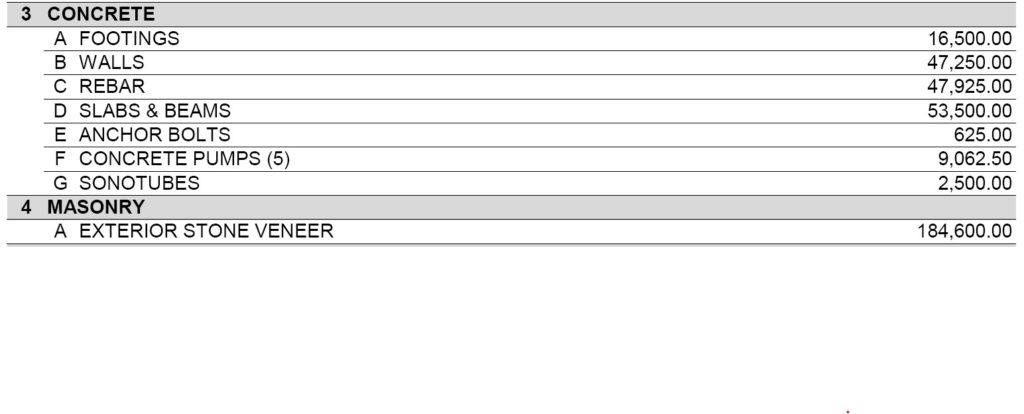

The answer to this question depends on the contractor! Sometimes, we work with contractors who provide a very thorough line-by-line accounting of how much each batch of labor and materials will cost. They detail things like excavation, well drilling, septic install, framing labor and materials, and specific finishes. As architects, we love this way of bidding. It gives us and our clients confidence that every item has been considered and accounted for. It also makes our value engineering process much more straightforward, as we can find both little and big places to save on cost. However, this bidding process is typically done by larger contractors with more resources. This usually means that there are more overhead costs involved on the project.

On smaller projects, or when working with smaller contractors, we often will get a bid with broader categories. For example, we may get a larger number that encompasses Site Work. This typically includes things like tree clearing, septic installation, excavation, and well drilling. This gives us an overall sense of what phases of construction might be costing more or less, but we have fewer specifics on lumber prices, concrete costs and individual trades.

Of course, there are things that are universal on a bid. Clients should expect to see a total for the project, as well as a breakdown of what overhead, supervision and percentage fees a contractor is charging on top of actual construction cost. Similar to our architecture fees, these cover the costs of doing things like bidding. It also might cover sourcing materials, coordinating subcontractors, managing the budget, keeping track of the construction schedule. Most importantly, it helps to ensure that everything is built to a high standard.

Bid Analysis and Comparisons

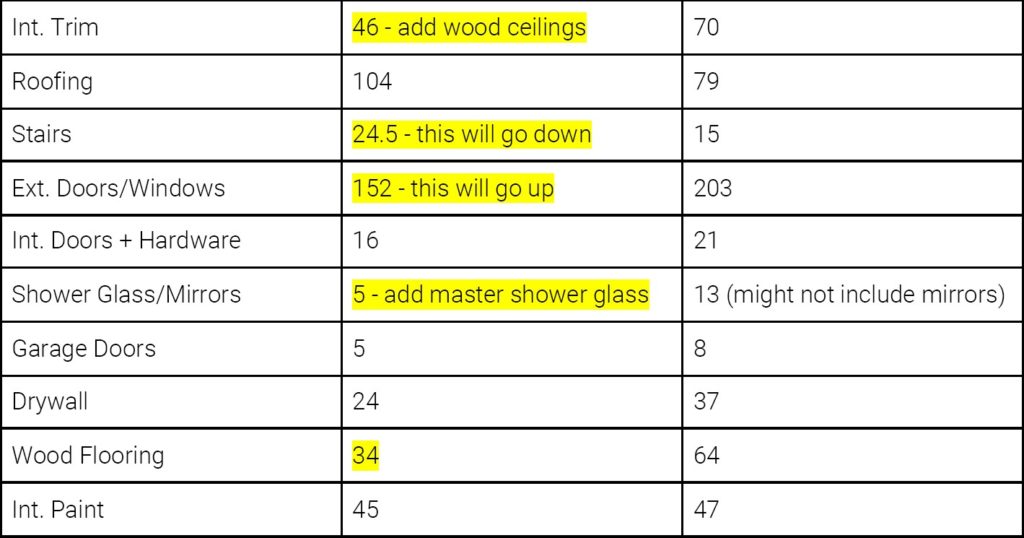

Sometimes, if we know a Contractor will be a great fit for the project and the client, we’ll only get one bid. More commonly, clients will ask us to send our drawings to multiple contractors to get a price comparison between them. Depending on the market, it may take between 4 and 8 weeks to receive bids. Once we do, we’ll typically sit down in our office and draw comparisons between the bids. It typically becomes clear where one contractor may have missed a detail or where one is pricing a higher cost material than the other.

However, we urge our clients to make a contractor selection not based solely on bidding estimates. The relationship between a client and a contractor is equally important. Consider a meeting with a contractor similar to a job interview. The contractor is interviewing you to evaluate how it might be to work with you, and you’re interviewing a contractor to see if you’ll enjoy working with them. This can be a question of personality, examples of prior work, or their approach to bidding. There are many reasons a client may choose to work with one contractor over another. We are always happy to advise clients on the best choice for them.

Value Engineering

Particularly right now, the construction market is more variable than we are used to. Subcontractors are able to charge more for their services because demand is high and raw material costs are fluctuating rapidly due to supply chain problems and shipping delays. We’ve found that while we always include value engineering as part of our bidding process, it has become even more critical to do so in the past year. Recently, we’ve had a number of projects in our office come in above the expected budget. Understandably, clients can be disappointed – and surprised – at the numbers that come back. For us, it’s an opportunity to rely on our relationship with our clients and have conversations about what matters most to them about their home.

We’ve come to learn that over the course of design phases, both our team and our clients will add finish selections or design elements that they would love to have but that they don’t consider essential. We do so with the intention of getting a bid and seeing where the numbers fall. This allows clients to make informed decisions. Does it feel worth it to have that stunning light fixture, or would they rather spend the money elsewhere?

Sometimes, these choices go beyond just finishes and fixture selections. As architects, we come prepared to this phase with smart, constructive solutions to lower the cost of the project. We might suggest lowering a roofline – perhaps eliminating clerestory windows and reducing the cost of framing structure. We might propose shifting the plan to simplify a concrete foundation or shrink a bedroom to tighten the square footage. Sometimes, clients will decide that it is ultimately worth the extra cost to keep these features, while in other instances they decide that they would rather have a tighter, more cost-effective home.

Permitting

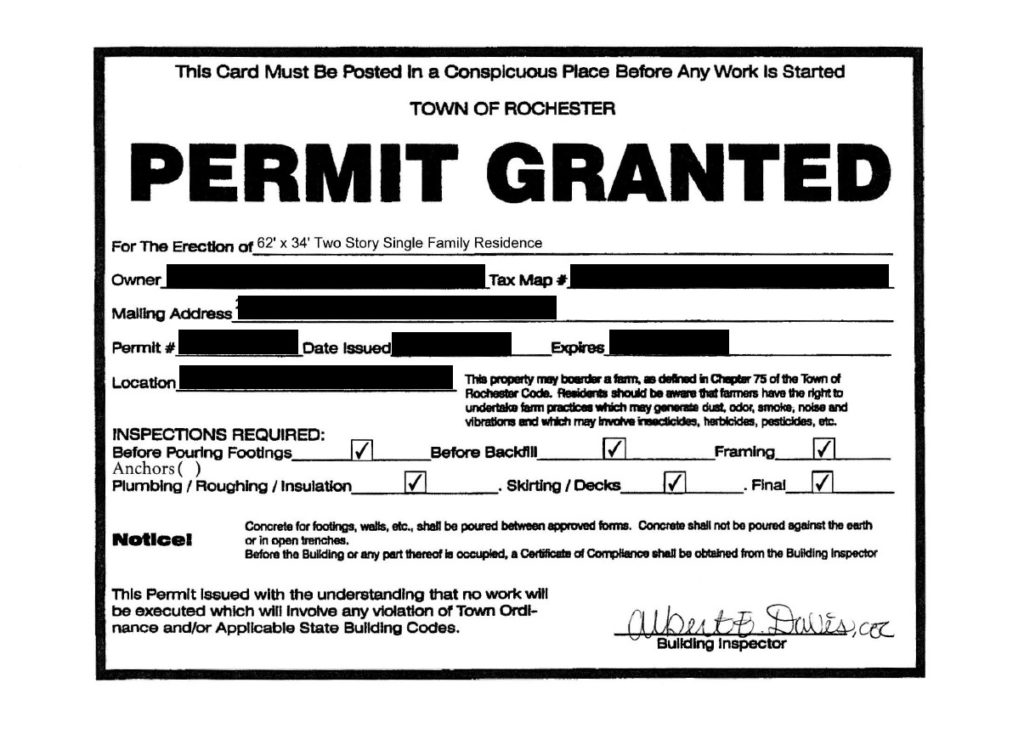

Like bidding, permitting can happen at a number of different moments. If bids come back close to our target budget, we will often immediately apply for a permit. If we need to spend some time value engineering the project, we will revise our drawings before submitting them to the town Building Department. Typically, the contractor and client will apply for the permit and we will submit drawings. This tends to depend on the project and on our relationship to the contractor and the particular Building Department.

Permitting can take anywhere from 2 weeks to as many as 2 or 3 months. Shorter timelines are typical if we are familiar with the Town and its permit application process and drawing requirements. Longer timelines should be anticipated in the cases where a Town requests additional information from a civil, mechanical or structural engineer, or from our architectural team. Additional information in upstate New York might include a more detailed site survey or stormwater drainage plan. In Tampa, Florida it often entails more developed details and specific product information for hurricane safety.

Regardless of how long it takes, we’re always very excited to receive a Building Permit. It signals that we are ready to move forward into our longest phase – Construction Administration. Keep an eye out for our next post in the series to find out why architects like to stay involved in this phase and how we help facilitate requests for additional information and adjustments that are made during the building process.

ICYMI:

Illustrating Our Process: Schematic Design

Illustrating Our Process: Exterior Design Development

Illustrating Our Process: Interior Design Development